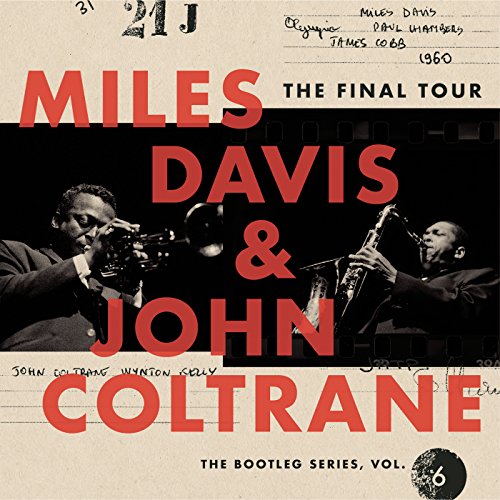

The Final Tour: The Bootleg Series, Vol. 6

This compilation (P) 2018 Columbia Records, a division of Sony Music Entertainment

Artist bios

A monumental innovator, icon, and maverick, trumpeter Miles Davis helped define the course of jazz as well as popular culture in the 20th century, bridging the gap between bebop, modal music, funk, and fusion. Throughout most of his 50-year career, Davis played the trumpet in a lyrical, introspective style, often employing a stemless Harmon mute to make his sound more personal and intimate. It was a style that, along with his brooding stage persona, earned him the nickname "Prince of Darkness." However, Davis proved to be a dazzlingly protean artist, moving into fiery modal jazz in the '60s and electrified funk and fusion in the '70s, drenching his trumpet in wah-wah pedal effects along the way. More than any other figure in jazz, Davis helped establish the direction of the genre with a steady stream of boundary-pushing recordings, among them 1957's chamber jazz album Birth of the Cool (which collected recordings from 1949-1950), 1959's modal masterpiece Kind of Blue, 1960's orchestral album Sketches of Spain, and 1970's landmark fusion recording Bitches Brew. Davis' own playing was obviously at the forefront of those changes, but he also distinguished himself as a bandleader, regularly surrounding himself with sidemen and collaborators who likewise moved in new directions, including the luminaries John Coltrane, Herbie Hancock, Bill Evans, Wayne Shorter, Chick Corea, and many more. While he remains one of the most referenced figures in jazz, a major touchstone for generations of trumpeters (including Wynton Marsalis, Chris Botti, and Nicholas Payton), his music reaches far beyond the jazz tradition, and can be heard in the genre-bending approach of performers across the musical spectrum, ranging from funk and pop to rock, electronica, hip-hop, and more.

Born in 1926, Davis was the son of dental surgeon, Dr. Miles Dewey Davis, Jr., and a music teacher, Cleota Mae (Henry) Davis, and grew up in the Black middle class of East St. Louis after the family moved there shortly after his birth. He became interested in music during his childhood and by the age of 12 began taking trumpet lessons. While still in high school, he got jobs playing in local bars and at 16 was playing gigs out of town on weekends. At 17, he joined Eddie Randle's Blue Devils, a territory band based in St. Louis. He enjoyed a personal apotheosis in 1944, just after graduating from high school, when he saw and was allowed to sit in with Billy Eckstine's big band, which was playing in St. Louis. The band featured trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie and saxophonist Charlie Parker, the architects of the emerging bebop style of jazz, which was characterized by fast, inventive soloing and dynamic rhythm variations.

It is striking that Davis fell so completely under Gillespie and Parker's spell, since his own slower and less flashy style never really compared to theirs. But bebop was the new sound of the day, and the young trumpeter was bound to follow it. He did so by leaving the Midwest to attend the Institute of Musical Art in New York City (renamed Juilliard) in September 1944. Shortly after his arrival in Manhattan, he was playing in clubs with Parker, and by 1945 he had abandoned his academic studies for a full-time career as a jazz musician, initially joining Benny Carter's band and making his first recordings as a sideman. He played with Eckstine in 1946-1947 and was a member of Parker's group in 1947-1948, making his recording debut as a leader on a 1947 session that featured Parker, pianist John Lewis, bassist Nelson Boyd, and drummer Max Roach. This was an isolated date, however, and Davis spent most of his time playing and recording behind Parker. But in the summer of 1948, he organized a nine-piece band with an unusual horn section. In addition to himself, it featured an alto saxophone, a baritone saxophone, a trombone, a French horn, and a tuba. This nonet, employing arrangements by Gil Evans and others, played for two weeks at the Royal Roost in New York in September. Earning a contract with Capitol Records, the band went into the studio in January 1949 for the first of three sessions and produced 12 tracks that attracted little attention at first. The band's relaxed sound, however, affected the musicians who played it, among them Kai Winding, Lee Konitz, Gerry Mulligan, John Lewis, J.J. Johnson, and Kenny Clarke, and it had a profound influence on the development of the cool jazz style on the West Coast. (In February 1957, Capitol finally issued the tracks together on an LP called Birth of the Cool.)

Davis, meanwhile, had moved on to co-leading a band with pianist Tadd Dameron in 1949, and the group took him out of the country for an appearance at the Paris Jazz Festival in May. But the trumpeter's progress was impeded by an addiction to heroin that plagued him in the early '50s. His performances and recordings became more haphazard, but in January 1951 he began a long series of recordings for the Prestige label that became his main recording outlet for the next several years. He managed to kick his habit by the middle of the decade, and he made a strong impression playing "'Round Midnight" at the Newport Jazz Festival in July 1955, a performance that led major-label Columbia to sign him. The prestigious contract allowed him to put together a permanent band, and he organized a quintet featuring saxophonist John Coltrane, pianist Red Garland, bassist Paul Chambers, and drummer Philly Joe Jones, who began recording his Columbia debut, 'Round About Midnight, in October.

As it happened, however, he had a remaining five albums on his Prestige contract, and over the next year he was forced to alternate his Columbia sessions with sessions for Prestige to fulfill this previous commitment. The latter resulted in the Prestige albums The New Miles Davis Quintet, Cookin', Workin', Relaxin', and Steamin', making Davis' first quintet one of his better-documented outfits. In May 1957, just three months after Capitol released the Birth of the Cool LP, Davis again teamed with arranger Gil Evans for his second Columbia LP, Miles Ahead. Playing flügelhorn, Davis fronted a big band on music that extended the Birth of the Cool concept and even had classical overtones. Released in 1958, the album was later inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame, intended to honor recordings made before the Grammy Awards were instituted in 1959.

In December 1957, Davis returned to Paris, where he improvised the background music for the film L'Ascenseur pour l'Echafaud. Jazz Track, an album containing this music, earned him a 1960 Grammy nomination for Best Jazz Performance, Solo or Small Group. He added saxophonist Cannonball Adderley to his group, creating the Miles Davis Sextet, which recorded Milestones in April 1958. Shortly after this recording, Red Garland was replaced on piano by Bill Evans and Jimmy Cobb took over for Philly Joe Jones on drums. In July, Davis again collaborated with Gil Evans and an orchestra on an album of music from Porgy and Bess. Back in the sextet, Davis began to experiment with modal playing, basing his improvisations on scales rather than chord changes.

This led to his next band recording, Kind of Blue, in March and April 1959, an album that became a landmark in modern jazz and the most popular album of Davis' career, eventually selling over two million copies, a phenomenal success for a jazz record. In sessions held in November 1959 and March 1960, Davis again followed his pattern of alternating band releases and collaborations with Gil Evans, recording Sketches of Spain, containing traditional Spanish music and original compositions in that style. The album earned Davis and Evans Grammy nominations in 1960 for Best Jazz Performance, Large Group, and Best Jazz Composition, More Than 5 Minutes; they won in the latter category.

By the time Davis returned to the studio to make his next band album in March 1961, Adderley had departed, Wynton Kelly had replaced Bill Evans at the piano, and John Coltrane had left to begin his successful solo career, being replaced by saxophonist Hank Mobley (following the brief tenure of Sonny Stitt). Nevertheless, Coltrane guested on a couple of tracks of the album, called Someday My Prince Will Come. The record made the pop charts in March 1962, but it was preceded into the best-seller lists by the Davis quintet's next recording, the two-LP set Miles Davis in Person (Friday & Saturday Nights at the Blackhawk, San Francisco), recorded in April. The following month, Davis recorded another live show, as he and his band were joined by an orchestra led by Gil Evans at Carnegie Hall in May. The resulting Miles Davis at Carnegie Hall was his third LP to reach the pop charts, and it earned Davis and Evans a 1962 Grammy nomination for Best Jazz Performance by a Large Group, Instrumental. Davis and Evans teamed up again in 1962 for what became their final collaboration, Quiet Nights. The album was not issued until 1964, when it reached the charts and earned a Grammy nomination for Best Instrumental Jazz Performance by a Large Group or Soloist with Large Group.

In 1996, Columbia Records released a six-CD box set, Miles Davis & Gil Evans: The Complete Columbia Studio Recordings, that won the Grammy for Best Historical Album. Quiet Nights was preceded into the marketplace by Davis' next band effort, Seven Steps to Heaven, recorded in the spring of 1963 with an entirely new lineup consisting of saxophonist George Coleman, pianist Victor Feldman, bassist Ron Carter, and drummer Frank Butler. During the sessions, Feldman was replaced by Herbie Hancock and Butler by Tony Williams. The album found Davis making a transition to his next great group, of which Carter, Hancock, and Williams would be members. It was another pop chart entry that earned 1963 Grammy nominations for both Best Instrumental Jazz Performance by a Soloist or Small Group and Best Instrumental Jazz Performance by a Large Group. The quintet followed with two live albums, Miles Davis in Europe, recorded in July 1963, which made the pop charts and earned a 1964 Grammy nomination for Best Instrumental Jazz Performance by a Small Group or Soloist with Small Group, and My Funny Valentine, recorded in February 1964 and released in 1965, when it reached the pop charts.

By September 1964, the final member of the classic Miles Davis Quintet of the '60s was in place with the addition of saxophonist Wayne Shorter to the team of Davis, Carter, Hancock, and Williams. While continuing to play standards in concert, this unit embarked on a series of albums of original compositions contributed by the bandmembers themselves, starting in January 1965 with E.S.P., followed by Miles Smiles (1967 Grammy nomination for Best Instrumental Jazz Performance by a Small Group or Soloist with Small Group [7 or Fewer]), Sorcerer, Nefertiti, Miles in the Sky (1968 Grammy nomination for Best Instrumental Jazz Performance by a Small Group or Soloist with Small Group), and Filles de Kilimanjaro. By the time of Miles in the Sky, the group had begun to turn to electric instruments, presaging Davis' next stylistic turn. By the final sessions for Filles de Kilimanjaro in September 1968, Hancock had been replaced by Chick Corea and Carter by Dave Holland. But Hancock, along with pianist Joe Zawinul and guitarist John McLaughlin, participated on Davis' next album, In a Silent Way (1969), which returned the trumpeter to the pop charts for the first time in four years and earned him another small-group jazz performance Grammy nomination. With his next album, Bitches Brew, Davis turned more overtly to a jazz-rock style. Though certainly not conventional rock music, Davis' electrified sound attracted a young, non-jazz audience while putting off traditional jazz fans.

Bitches Brew, released in March 1970, reached the pop Top 40 and became Davis' first album to be certified gold. It also earned a Grammy nomination for Best Instrumental Arrangement and won the Grammy for large-group jazz performance. He followed it with such similar efforts as Miles Davis at Fillmore East (1971 Grammy nomination for Best Jazz Performance by a Group), A Tribute to Jack Johnson, Live-Evil, On the Corner, and In Concert, all of which reached the pop charts. Meanwhile, Davis' former sidemen became his disciples in a series of fusion groups: Corea formed Return to Forever, Shorter and Zawinul led Weather Report, and McLaughlin and former Davis drummer Billy Cobham organized the Mahavishnu Orchestra. Starting in October 1972, when he broke his ankles in a car accident, Davis became less active in the early '70s, and in 1975 he gave up recording entirely due to illness, undergoing surgery for hip replacement later in the year. Five years passed before he returned to action by recording The Man with the Horn in 1980 and going back to touring in 1981.

By now, he was an elder statesman of jazz, and his innovations had been incorporated into the music, at least by those who supported his eclectic approach. He was also a celebrity whose appeal extended far beyond the basic jazz audience. He performed on the worldwide jazz festival circuit and recorded a series of albums that made the pop charts, including We Want Miles (1982 Grammy Award for Best Jazz Instrumental Performance by a Soloist), Star People, Decoy, and You're Under Arrest. In 1986, after 30 years with Columbia, he switched to Warner Bros. and released Tutu, which won him his fourth Grammy for Best Jazz Instrumental Performance.

Aura, an album he had recorded in 1984, was released by Columbia in 1989 and brought him his fifth Grammy for Best Jazz Instrumental Performance by a Soloist (on a Jazz Recording). Davis surprised jazz fans when, on July 8, 1991, he joined an orchestra led by Quincy Jones at the Montreux Jazz Festival to perform some of the arrangements written for him in the late '50s by Gil Evans; he had never previously looked back at an aspect of his career. He died of pneumonia, respiratory failure, and a stroke within months. Doo-Bop, his last studio album, appeared in 1992. It was a collaboration with rapper Easy Mo Bee, and it won a Grammy for Best Rhythm & Blues Instrumental Performance, with the track "Fantasy" nominated for Best Jazz Instrumental Solo. Released in 1993, Miles & Quincy Live at Montreux won Davis his seventh Grammy for Best Large Jazz Ensemble Performance.

Miles Davis took an all-inclusive, constantly restless approach to jazz that won him accolades and earned him controversy during his lifetime. It was hard to recognize the bebop acolyte of Charlie Parker in the flamboyantly dressed leader who seemed to keep one foot on a wah-wah pedal and one hand on an electric keyboard in his later years. But he did much to popularize jazz, reversing the trend away from commercial appeal that bebop started. And whatever the fripperies and explorations, he retained an ability to play moving solos that endeared him to audiences and demonstrated his affinity with tradition. He is a reminder of the music's essential quality of boundless invention, using all available means. Twenty-four years after Davis' death, he was the subject of Miles Ahead, a biopic co-written and directed by Don Cheadle, who also portrayed him. Its soundtrack functioned as a career overview with additional music provided by pianist Robert Glasper and associates. Additionally, Glasper enlisted many of his collaborators to help record Everything's Beautiful, a separate release that incorporated Davis' master recordings and outtakes into new compositions. In 2020, the trumpeter was also the focus of director Stanley Nelson's documentary Miles Davis: Birth of the Cool, which showcased music from throughout Davis' career. Also included on the documentary's soundtrack was a newly produced track, "Hail to the Real Chief," constructed out of previously unreleased Davis recordings by the trumpeter's fusion-era bandmates drummer Lenny White and drummer (and nephew) Vince Wilburn, Jr. ~ William Ruhlmann

A towering musical figure of the 20th century, saxophonist John Coltrane reset the parameters of jazz during his decade as a leader. At the outset, he was a vigorous practitioner of hard bop, gaining prominence as a sideman for Miles Davis before setting out as a leader in 1957, when he released Coltrane on Prestige and Blue Train on Blue Note. Coltrane quickly expanded his horizons, pioneering a technique critic Ira Gitler dubbed "sheets of sound," consisting of the saxophonist playing a flurry of notes on his tenor within the confines of a few chords. During his last days with Davis, along with his earliest records for Atlantic, Coltrane leaned into this technique, but as he developed his career as a leader in the early '60s, he also turned lyrical. His sweet, fluid soprano sax distinguished My Favorite Things, which helped turn the album into a standard upon its release in 1961, but Coltrane soon backed away from mainstream acceptance. Working with pianist McCoy Tyner, drummer Elvin Jones, and bassist Jimmy Garrison -- a band that would be labeled the "Classic Quartet" -- Coltrane entered a fearless exploratory phase, explicitly incorporating his spiritual quest into his experimental music. A Love Supreme, an album released on Impulse! in 1965, marked the popular height of this period, but Coltrane continued to voyage to the outer edges of jazz in his final years, collaborating with Archie Shepp and Pharoah Sanders. Liver cancer ended his life prematurely: he died at the age of 40 in 1967, just ten years after his first LP as a leader -- but Coltrane's legacy was so varied and rich, he remained the touchstone for creativity in jazz for decades after his passing.

Coltrane was the son of John R. Coltrane, a tailor and amateur musician, and Alice (Blair) Coltrane. Two months after his birth, his maternal grandfather, the Reverend William Blair, was promoted to presiding elder in the A.M.E. Zion Church and moved his family, including his infant grandson, to High Point, North Carolina, where Coltrane grew up. Shortly after he graduated from grammar school in 1939, his father, his grandparents, and his uncle died, leaving him to be raised in a family consisting of his mother, his aunt, and his cousin. His mother worked as a domestic to support the family. The same year, he joined a community band in which he played clarinet and E flat alto horn; he took up the alto saxophone in his high school band. During World War II, Coltrane's mother, aunt, and cousin moved north to New Jersey to seek work, leaving him with family friends; in 1943, when he graduated from high school, he too headed north, settling in Philadelphia. Eventually, the family was reunited there.

While taking jobs outside music, Coltrane briefly attended the Ornstein School of Music and studied at Granoff Studios. He also began playing in local clubs. In 1945, he was drafted into the navy and stationed in Hawaii. He never saw combat, but he continued to play music and, in fact, made his first recording with a quartet of other sailors on July 13, 1946. A performance of Tadd Dameron's "Hot House," it was released in 1993 on the Rhino Records anthology The Last Giant. Coltrane was discharged in the summer of 1946 and returned to Philadelphia. That fall, he began playing in the Joe Webb Band. In early 1947, he switched to the King Kolax Band. During the year, he switched from alto to tenor saxophone. One account claims that this was as the result of encountering alto saxophonist Charlie Parker and feeling the better-known musician had exhausted the possibilities on the instrument; another says that the switch occurred simply because Coltrane next joined a band led by Eddie "Cleanhead" Vinson, who was an alto player, forcing Coltrane to play tenor. He moved on to Jimmy Heath's group in mid-1948, staying with the band, which evolved into the Howard McGhee All Stars until early 1949, when he returned to Philadelphia. That fall, he joined a big band led by Dizzy Gillespie, remaining until the spring of 1951, by which time the band had been trimmed to a septet. On March 1, 1951, he took his first solo on record during a performance of "We Love to Boogie" with Gillespie.

At some point during this period, Coltrane became a heroin addict, which made him more difficult to employ. He played with various bands, mostly around Philadelphia, during the early '50s, his next important job coming in the spring of 1954, when Johnny Hodges, temporarily out of the Duke Ellington band, hired him. But he was fired because of his addiction in September 1954. He returned to Philadelphia, where he was playing when he was hired by Miles Davis a year later. His association with Davis was the big break that finally established him as an important jazz musician. Davis, a former drug addict himself, had kicked his habit and gained recognition at the Newport Jazz Festival in July 1955, resulting in a contract with Columbia Records and the opportunity to organize a permanent band, which, in addition to him and Coltrane, consisted of pianist Red Garland, bassist Paul Chambers, and drummer "Philly" Joe Jones. This unit immediately began to record extensively, not only because of the Columbia contract, but also because Davis had signed with the major label before fulfilling a deal with jazz independent Prestige Records that still had five albums to run. The trumpeter's Columbia debut, 'Round About Midnight, which he immediately commenced recording, did not appear until March 1957. The first fruits of his association with Coltrane came in April 1956 with the release of The New Miles Davis Quintet (aka Miles), recorded for Prestige on November 16, 1955. During 1956, in addition to his recordings for Columbia, Davis held two marathon sessions for Prestige to fulfill his obligation to the label, which released the material over a period of time under the titles Cookin' (1957), Relaxin' (1957), Workin' (1958), and Steamin' (1961).

Coltrane's association with Davis inaugurated a period when he began to frequently record as a sideman. Davis may have been trying to end his association with Prestige, but Coltrane began appearing on many of the label's sessions. After he became better known in the '60s, Prestige and other labels began to repackage this work under his name, as if he had been the leader, a process that has continued to the present day. (Prestige was acquired by Fantasy Records in 1972, and many of the recordings in which Coltrane participated have been reissued on Fantasy's Original Jazz Classics [OJC] imprint.)

Coltrane tried and failed to kick heroin in the summer of 1956, and in October, Davis fired him, though the trumpeter had relented and taken him back by the end of November. Early in 1957, Coltrane formally signed with Prestige as a solo artist, though he remained in the Davis band and also continued to record as a sideman for other labels. In April, Davis fired him again. This may have given him the impetus to finally kick his drug habit, and freed of the necessity of playing gigs with Davis, he began to record even more frequently. On May 31, 1957, he finally made his recording debut as a leader, putting together a pickup band consisting of trumpeter Johnny Splawn, baritone saxophonist Sahib Shihab, pianists Mal Waldron and Red Garland (on different tracks), bassist Paul Chambers, and drummer Al "Tootie" Heath. They cut an album Prestige simply titled Coltrane upon release in September 1957. (It has since been reissued under the title First Trane.)

In June 1957, Coltrane joined the Thelonious Monk Quartet, consisting of Monk on piano, Wilbur Ware on bass, and Shadow Wilson on drums. During this period, he developed a technique of playing several notes at once, and his solos began to go on longer. In August, he recorded material belatedly released on the Prestige albums Lush Life (1960) and The Last Trane (1965), as well as the material for John Coltrane with the Red Garland Trio, released later in the year. (It was later reissued under the title Traneing In.) But Coltrane's second album to be recorded and released contemporaneously under his name alone was cut in September for Blue Note Records. This was Blue Train, featuring trumpeter Lee Morgan, trombonist Curtis Fuller, pianist Kenny Drew, and the Miles Davis rhythm section of Chambers and "Philly" Joe Jones; it was released in December 1957. That month, Coltrane rejoined Davis, playing in what was now a sextet that also featured Cannonball Adderley. In January 1958, he led a recording session for Prestige that produced tracks later released on Lush Life, The Last Trane, and The Believer (1964). In February and March, he recorded Davis' album Milestones, released later in 1958. In between the sessions, he cut his third album to be released under his name alone, Soultrane, issued in September by Prestige. Also in March 1958, he cut tracks as a leader that would be released later on the Prestige collection Settin' the Pace (1961). In May, he again recorded for Prestige as a leader, though the results would not be heard until the release of Black Pearls in 1964.

Coltrane appeared as part of the Miles Davis group at the Newport Jazz Festival in July 1958. The band's set was recorded and released in 1964 on an LP also featuring a performance by Thelonious Monk as Miles & Monk at Newport. In 1988, Columbia reissued the material on an album called Miles & Coltrane. The performance inspired a review in Down Beat, the leading jazz magazine, that was an early indication of the differing opinions on Coltrane that would be expressed throughout the rest of his career and long after his death. The review referred to his "angry tenor," which, it said, hampered the solidarity of the Davis band. The review led directly to an article published in the magazine on October 16, 1958, in which critic Ira Gitler defended the saxophonist and coined the much-repeated phrase "sheets of sound" to describe his playing.

Coltrane's next Prestige session as a leader occurred in July 1958 and resulted in tracks later released on the albums Standard Coltrane (1962), Stardust (1963), and Bahia (1965). All of these tracks were later compiled on a reissue called The Stardust Session. He did a final session for Prestige in December 1958, recording tracks later released on The Believer, Stardust, and Bahia. This completed his commitment to the label, and he signed to Atlantic Records, making his first recording for his new employers on January 15, 1959 with a session on which he was co-billed with vibes player Milt Jackson, though it did not appear until 1961 with the LP Bags and Trane. In March and April 1959, Coltrane participated with the Davis group on the album Kind of Blue. Released on August 17, 1959, this landmark album known for its "modal" playing (improvisations based on scales or "modes," rather than chords) became one of the best-selling and most-acclaimed recordings in the history of jazz.

By the end of 1959, Coltrane had recorded what would be his Atlantic debut, Giant Steps, released in early 1960. The album, consisting entirely of Coltrane compositions, in a sense marked his real debut as a leading jazz performer, even though the 33-year-old musician had released three previous solo albums and made numerous other recordings. His next Atlantic album, Coltrane Jazz, was mostly recorded in November and December 1959 and released in February 1961. In April 1960, he finally left the Davis band and formally launched his solo career, beginning an engagement at the Jazz Gallery in New York, accompanied by pianist Steve Kuhn (soon replaced by McCoy Tyner), bassist Steve Davis, and drummer Pete La Roca (later replaced by Billy Higgins and then Elvin Jones). During this period, he increasingly played soprano saxophone as well as tenor.

In October 1960, Coltrane recorded a series of sessions for Atlantic that would produce material for several albums, including a final track used on Coltrane Jazz and tunes used on My Favorite Things (March 1961), Coltrane Plays the Blues (July 1962), and Coltrane's Sound (June 1964). His soprano version of "My Favorite Things," from the Richard Rodgers/Oscar Hammerstein II musical The Sound of Music, would become a signature song for him. During the winter of 1960-1961, bassist Reggie Workman replaced Steve Davis in his band, and saxophone and flute player Eric Dolphy gradually became a member of the group.

In the wake of the commercial success of "My Favorite Things," Coltrane's star rose, and he was signed away from Atlantic as the flagship artist of the newly formed Impulse! Records label, an imprint of ABC-Paramount, though in May he cut a final album for Atlantic, Olé (February 1962). The following month, he completed his Impulse! debut, Africa/Brass. By this time, his playing was frequently in a style alternately dubbed "avant-garde," "free," or "The New Thing." Like Ornette Coleman, he played seemingly formless, extended solos that some listeners found tremendously impressive, and others decried as noise. In November 1961, John Tynan, writing in Down Beat, referred to Coltrane's playing as "anti-jazz." That month, however, Coltrane recorded one of his most celebrated albums, Live at the Village Vanguard, an LP paced by the 16-minute improvisation "Chasin' the Trane."

Between April and June 1962, Coltrane cut his next Impulse! studio album, another release called simply Coltrane when it appeared later in the year. Working with producer Bob Thiele, he began to do extensive studio sessions, far more than Impulse! could profitably release at the time, especially with Prestige and Atlantic still putting out their own archival albums. But the material would serve the label well after the saxophonist's untimely death. Thiele acknowledged that Coltrane's next three Impulse! albums to be released, Ballads, Duke Ellington and John Coltrane, and John Coltrane with Johnny Hartman (all 1963), were recorded at his behest to quiet the critics of Coltrane's more extreme playing. Impressions (1963), drawn from live and studio recordings made in 1962 and 1963, was a more representative effort, as was 1964's Live at Birdland, also a combination of live and studio tracks, despite its title. But Crescent, also released in 1964, seemed to find a middle ground between traditional and free playing, and was welcomed by critics. This trend was continued with 1965's A Love Supreme, one of Coltrane's best-loved albums, which earned him two Grammy nominations, for Jazz Composition and Performance, and became his biggest-selling record. Also during the year, Impulse! released the standards collection The John Coltrane Quartet Plays... and another album of "free" playing, Ascension, as well as New Thing at Newport, a live album consisting of one side by Coltrane and the other by Archie Shepp.

The year 1966 saw the release of the albums Kulu Se Mama and Meditations, Coltrane's last recordings to appear during his lifetime, though he had finished and approved release for his next album, Expression, the Friday before his death in July 1967. He died suddenly of liver cancer, entering the hospital on a Sunday and expiring in the early morning hours of the next day. He had left behind a considerable body of unreleased work that came out in subsequent years, including "Live" at the Village Vanguard Again! (1967), Om (1967), Cosmic Music (1968), Selflessness (1969), Transition (1969), Sun Ship (1971), Africa/Brass, Vol. 2 (1974), Interstellar Space (1974), and First Meditations (For Quartet) (1977), all on Impulse!

Compilations and releases of archival live recordings brought him a series of Grammy nominations, including Best Jazz Performance for the Atlantic album The Coltrane Legacy in 1970; Best Jazz Performance, Group, and Best Jazz Performance, Soloist, for "Giant Steps" from the Atlantic album Alternate Takes in 1974; and Best Jazz Performance, Group, and Best Jazz Performance, Soloist, for Afro Blue Impressions in 1977. He won the 1981 Grammy for Best Jazz Performance, Soloist, for Bye Bye Blackbird, an album of recordings made live in Europe in 1962, and he was given the Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award in 1992, 25 years after his death.

Even more previously unreleased material has surfaced since then, including the discovery of the Monk and Coltrane live concert At Carnegie Hall and a complete version of his 1966 Seattle concert, Offering: Live at Temple University. The saxophonist was also the subject of director John Scheinfeld's acclaimed 2017 film Chasing Trane: The John Coltrane Documentary. In 2018, Impulse! released Both Directions at Once: The Lost Album, an archival release documenting a previously unheard session from 1963. The next year brought another unreleased album, Blue World, which dated from a June 1964 session recorded in between the sessions for Crescent and A Love Supreme.

John Coltrane is sometimes described as one of jazz's most influential musicians, and certainly there are other artists whose playing is heavily indebted to him. Perhaps more to the point, Coltrane is influential by example, inspiring musicians to experiment, take chances, and devote themselves to their craft. The controversy about his work has never died down, but partially as a result, his name lives on and his recordings continue to remain available and to be reissued frequently. ~ William Ruhlmann

Customer Reviews

How are ratings calculated?